More important is the way that Spinney's book draws out the way that the 1918 pandemic hit along lines of class, racism and colonial division. The very name of the disease arises out of the way that the warring nations kept news about disease hidden, and only neutral Spain told the truth. But the disease was spread by soldiers travelling too and from the front - perhaps even brought to Europe by American troops heading to the trenches. It reached Australia after their successful initial quarantine kept out the first peak, but returning soldiers were let in. Hundreds of thousands died.

However Spinney doesn't neglect regions outside of Europe - a problem that often occurs when the Spanish Flu is discussed. There is a heart-breaking chapter about how the Flu destroyed whole communities in Alaska, leaving hundreds of orphans. Chapters on China and India are heart-breaking for the sheer scale of the devastation. And repeatedly we see that those who are poor, lack health-care and quality food die harder and in greater numbers than the rich. A case in point is from the wealthy areas of Paris. As Spinney explains:

Statisticians were foxed by their observation that the highest death rates in the French capital were recorded in the wealthiest neighbourhoods, until they realised who was dying there. The ones coughing behind the grand Haussmannian facades weren't the owners... but the servants... They worked fifteen-to-eighteen-hour days and often had to share their sleeping spaces with other servants... a quarter of all the women who died in Paris were maids.

The disease spread along the routes of capital - railways, shipping and transport - and may have played a roll in shaping some of the struggles that emerged against capitalism after World War One. Spinney notes the influence the disease had on the Indian Independence struggle for instance, the Russian Revolution and other social conflicts. However this bits were the weakest part of the book. I didn't feel particularly convinced of the argument that the disease "changed the world". However the author is much better when exploring the details of disease and society. This is where the lessons for today come from.

Spinney's history of the scientific battle to understand disease, viruses and vaccines is important and well written. However it is the parallels with today that will haunt readers, and her conclusions that emphasise the importance of social health care, funding and education. She notes:

The Spanish flu and subsequent pandemics demonstrated that, given the right incentives and training, health workers stay at their posts and honour their duty to treat, often at great risk to their personal safety. That work force therefore needs to be supported as much as possible and cared for in the event of illness. The best way to support them is to arm them with effective methods of surveillance and prophylaxis, and to make sure that they are dealing with an informed, compliant public. All three areas have seen huge advances since 1918, but there is still room for improvement.

She concludes, following a discussion about the moral of mandatory health measures (she points out that these don't work very well) that:

But if disease containment works best when people choose freely to comply, then people must be informed about the nature of the disease and the risk it poses. This is one reason why it's important to tell the story of the Spanish flu.

It's certainly one reason I read this book. Unfortunately perhaps it wasn't read widely enough in the brief period after its publication and the arrival of Covid-19. While demonstrating that disease (and medicine) are shaped by the reality of capitalist society, this is no call for revolution. Nonetheless Laura Spinney's book is engaging, detailed and sharp on the interaction between disease and society through a historical lens. Let us hope that lessons are drawn from this tragedy to prevent the three million deaths becoming just part of a much greater tragedy.

Related Reviews

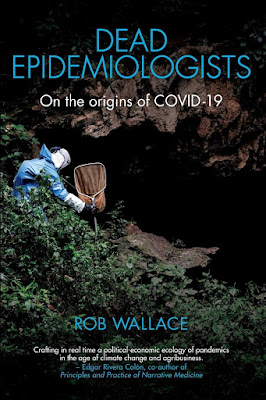

Wallace - Dead Epidemiologists: On the Origins of Covid-19

Harrison - Contagion: How Commerce has Spread Disease

Wallace - Big Farms Make Big Flu

Malm - Corona, Climate, Chronic Emergency: War Communism in the 21st Century

Davis - The Monster Enters

Quammen - Ebola: The Natural and Human History