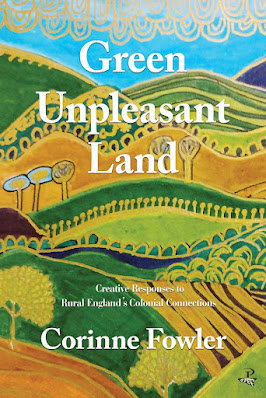

For her unflinching portrayal of the reality of the English countryside, Fowler has received plenty of criticism. In a hostile article the Daily Mail quoted the former, right-wing, Tory cabinet minister Peter Lilley as saying, "Arguably, it is she who has insulted her country by her book whose very title — Green Unpleasant Land — tells us what she thinks of her fellow citizens." Typically the Daily Mail headline claims that "gardening has its roots in racial injustice". It is a click-bait title designed to trigger the sort of apoplectic rage that the Mail's core readership excel in. It is also grossly unfair for Fowler's book is nuanced and detailed about the reality of the English countryside, gardening and its portrayal in literature. In fact Green Unpleasant Land is a remarkably interesting study of the English countryside, its history and the forces that shaped (and continue to shape) the landscape many of us, including Fowler, continue to enjoy.

The Drax wall is a useful entry point to Fowler's argument. She notes that it "provides a fitting metaphor for the link between empire overseas and enclosure at home". Far from being a idyllic place, the countryside, Fowler argues, was (is) a space of intense struggle over ownership and access. She notes the various class struggles against enclosure or for economic improvements and points out that this continues today. But despite this history, the image of a beautiful pastoral idyll continues. She says:

Industrialised farming and escalating environmental destruction ought to have made naïve visions of the countryside hard to sustain. Yet they have been sustained, and a succession of social histories, personal memoirs and political manifestos have criticised the continuing pastoral view.

In contrast she points to a whole number of books and studies that have demonstrated the exact opposite (including, full disclosure, one of my own books). In particular she looks at the close links between colonialism, racism and the countryside - which manifest both through economic issues such as land ownership and exclusion, to more overt racism directed to Black visitors. She argues that there has been a "collective amnesia about the role of empire", highlighting, for example W.G.Hoskins' classic work The Making of the English Landscape, which "makes no mention of empire".

Fowler dismisses "common misapprehensions about rural England: firstly, that it has nothing to do with colonialism and, secondly, that Black British and Asian British authors are disconnected from English rurality." She systematically examines the way that writers who have written about the countryside, or set novels within it, consider questions of colonialism and racism. There are some fascinating examples. In Walter Scott's 1814 novel Waverley, the Highlands are seen as populated by people compared by Scott to "natives of Africa and America, India and the Orient". Charlotte Brontë repeatedly hints at the "colonial connotations of Wuthering Heights". Descriptions of the moors frequently link the dirty, poverty stricken people to black faced "savages".

Yet the colonial linkage to the countryside is not just in fiction. Fowler shows how the nature of Empire shaped the countryside too. Drax's wall is one example. The profits from slavery allowed a new landowning bourgeoise to transform the landscape. The enclosures of land and the destruction of common rights, leading to the forcible destruction of the peasantry are part of a process where the primitive accumulation of wealth overseas helped kick start the evolution of capitalism back home. That's the economic context, but there were other examples. Slaves were brought back to England from overseas, sometimes to be black servants, a particularly appalling fashion. There were also black workers, traders, gardeners and escaped slaves in the countryside. The history opf the English countryside is far blacker than the Daily Mail would like.

The global transportation of plants as transformed gardens and farms in Europe. Fowler points out the role of slaves themselves in helping select and transport these plants for botanists, farmers and gardeners to enjoy. The knowledge and labour of enslaved black people and indigenous communities was essential to choosing the plants as well as providing the food to continue with slavery. Gardening may not have had its original roots in racial injustice as the Daily Mail claims Fowler says, but it was fundamentally shaped by slavery, colonialism and imperialism.

Fowler's book is subtitled Creative Responses to Rural England's Colonial Connections. These creative responses include the poetry, novels and essays of black writers whom Fowler examines in depth. The breadth of her coverage of these is remarkable and I found it impossible not to add to my list of books to read as a result. But Fowler also adds her own creativity to the discussion by responding to the themes and arguments in the book with a short story and some poetry of her own. I found these particularly insightful, and it the fact the book brings together the non-fiction and fictional form was both unusual and thought-provoking. I particularly enjoyed the poem about Kings Heath park in Birmingham which I know well. Her poem Green Unpleasant Land is about the response to Danny Boyle's London 2012 Olympic opening ceremony. In the opening chapter of the book Fowler examines the knee-jerk response to Boyle's placing of black people in the countryside and in the poem she has a raging commentator declare:

If you're still listening, here's my message:

to all you pc hand-wringers out there:

Jerusalem will never get built

if you corrupt our heritage

The erroneous belief that the English countryside is untainted by corruption, violence, racism, colonialism or class struggle is a deep-seated one. As Fowler points out, "they" have to keep reinventing it. Why? I think it serves two purposes. By removing the real history of the countryside, it becomes a continuous reservoir that the ruling class can draw upon to challenge progressive ideas. But it also offers something to individuals - escapism, hope, a challenge to the alienation of work and urban areas. We're sold a dream of Jerusalem outside the city, because without that dream, the reality is overcrowded housing, lack of jobs, poverty and polluted streets. Corinne Fowler's Green Unpleasant Land is a challenge to that narrative. It is readable, entertaining and honest, and deserves a wide readership if we are to really build Jerusalem.

Related Reviews

Howkins - The Death of Rural England

Groves - Sharpen the Sickle

Rackham - The History of the Countryside

Poskett - Horizons: A Global History of Science

Horn - Joseph Arch

No comments:

Post a Comment