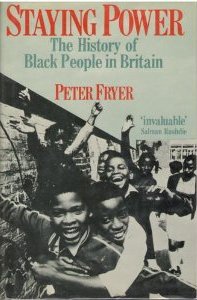

Peter Fryer was a socialist journalist of enormous reputation. As related in this obituary his experiences in Hungary during the 1956 uprising reporting for the Daily Worker led him to break from the British Communist Party. He remained active on the far left, joining a Trotskyist organisation where his talents as a writer continued to be demonstrated. I've reviewed a couple of his works, including his slightly eccentric Studies of English Prudery on this blog. Staying Power however is Peter Fryer's most important book, the culmination of a lifetimes reading, writing and research. While it covers an immense period, it concentrates on the 16th century onwards for this is when the role of black and asian people becomes most important for British history. In part this is because more and more black people are living in the British Isles, but it is also because it is during the first couple of centuries of this period that slavery becomes absolutely central the accumulation of wealth for British capitalism. It is during this period, to paraphrase Marx, that capital was born into the world, drenched in blood.

Beginning with the presence of black people amongst Roman legionnaires on Hadrian's Wall, Fryer relates much of this history through contemporary accounts, quotes and frequently the voices of black people themselves. These forgotten accounts are often powerful and heart rending - the stories of escaped slaves, people who failed to escape slavery, victims of racism and violence and occasionally those who fought back and escaped persecution or their chains.

As a socialist, Fryer's sympathies are with the oppressed, rather than the oppressor. In one of the two core chapters of the book, that on slavery, he discusses how slavery was ended, first in Britain and then in the colonies. Not for Fryer is this a result of the benevolent gentleman or the sympathetic judge. While both these figures make an appearance (Fryer is too rounded a historian to ignore their contributions) his explanation is rooted much more in the activities of ordinary people, men and women, black and white. Here for instance he describes the way that slavery was ended in Britain:

"if, contrary to popular belief, slavery in Britain was not outlawed by Mansfield in 1772, how in fact was it ended? The short answer is that black slaves in Britain voted with their feet. They had always... resisted by running away from their masters and mistresses. Helped and encouraged, and to some extent protected by the Mansfield decision, they had largely completed this process and freed themselves by the mid-1790s. This gradual self-emancipation is a matter of social rather than legal history..."

Fryer also understands that not all white people had the same attitudes to the small, but growing numbers of black people in Britain. Often those who fought and organised against slavery where the white working class, instinctively understanding that, the ruling class had an interest in dividing them and using racism to undermine their collective strength. Moral revulsion at slavery from ordinary people played its role - Fryer documents a number of accounts of escaped slaves being accepted into white working class communities and protected from their former masters, including a welsh mining community. But it was at periods of "working-class radicalism" that the abolitionist movement grew. This even went to the heart of the parts of Britain which had gained the most from slavery itself:

"The 1792 petition from Manchester, whose population was somewhat under 75,000 carried over 20,0000 signatures. Even Bristol had a petition. It was the spread of radical ideas amongst working people that had brought about this change".

Anti-slavery was part and parcel of radical activism. It was at the core, for instance, of the ideas coming out of the French Revolution and later of Chartism. This is not surprising, the racial ideas that justified slavery were in part a product of growing fear of rebellion at home, as Fryer points out, "there was an organic connection in nineteenth century Britain between the attitude the ruling class took to the 'natives; in its colonies and the attitude it took to the poor at home."

He continues:

"Though the Chartist movement evaporated after 1848, by the 1860s working people in Britain were once more challenging the political and economic power of those who ruled and employed them. Faced with this challenge, 'the proponents of social inequality slipped all the more readily into racial rhetoric'."

The second core chapter, and perhaps the most important is the one were Fryer shows how racism was consciously created and encouraged on the plantations. This invention of racism was needed to justify what was happening to the slaves and to allow slavery to continue. It was simply too profitable for the slave owners and traders, yet without racial justification for the slave trade, it would have been impossible to continue with it. In part this was pseudo-scientific racism, in part it was simply the extension and development of the myths and prejudices that existed about Africa and the non-white world. Africans were "lazy", "childlike" or "simple" and Fryer details the development of such racist ideas and how they spread through the British Empire. One of the reasons this is so crucial is that it demonstrates that racism (as opposed to prejudice or ignorance about black people) has not always existed. It is not some inherent part of human nature, rather a product of the need to make profit by trading in people from Africa.

As always there were those who argued against this, and Peter Fryer quotes one such man a minister, Morgan Godwyn in 1680, who pointed to the "economic basis and role of plantocracy racism". Godwyn's book argued that in dehumanising black people, slavery was justified. One aspect to this, was the way that slaves were denied religion, which served, as Godwyn points out, to;

"The issue whereof is, that as in the Negroe's all pretence to Religion is cut off, so their Owners are hereby set at Liberty, and freed from those importunate Scruples, which Conscience and better Advice might at any time happen to inject into their unsteadie Minds."

Godwyn believed that the "'public agents' for the West Indies, 'know know other God by Money, nor Religion but Profit'." That the first such blows against slavery were struck in the language of religion is no surprise. They were not to be the last.

Racism did not end with the abolition of slavery. Indeed racism was to prove, as the above quote demonstrates, too useful in dividing the working class. Fryer follows the story of the battles against racism, and the experiences of black people in Britain, through the 20th century. He shows how, despite forming an integral part of the armed forces during World War One, and increasingly being accepted into British life, racism reared its ugly head. As the War finished and black soldiers weren't needed, they were forgotten, deported or ignored. Fryer uncovers the forgotten history of the race riots when groups of white men attacked (often on a huge scale) black people, their homes and clubs. These riots, particularly those in Liverpool and Cardiff in 1919 were terrifying and the authorities looked the other way.

There is much more in Fryers book. He tells the stories of various attempts to build anti-colonial movements in the UK, or to support existing struggles elsewhere. On a lighter note he documents the stories of musicians, boxers and artists who came to Britain from the West Indies and Africa.

The book finishes, abruptly to the contemporary reader, in 1981 in the immediate aftermath of the riots that swept the country. Riots that were both a response to institutionalised racism and the poverty and unemployment that often goes with it. There are many echoes of this past today, not least in the experience of the 2011 riots in Britain. The problems that Fryer identifies in 20th century capitalism for Black people have not disappeared in the early 21st century.

As a social history this book has no equal. Fryer's scholarship is detailed, but his work is immensely readable. It is a book that should be on the shelf of everyone committed to fighting racism, every socialist and every trade unionist. It is a singular history of Britain that demonstrates the way that ordinary people, black and white, have been the victims of the quest for profits, but how they have also organised to improve fight for a better world.

Related Reviews

Fryer - Hungarian Tragedy

Fryer - Mrs Grundy: Studies in English Prudery

No comments:

Post a Comment